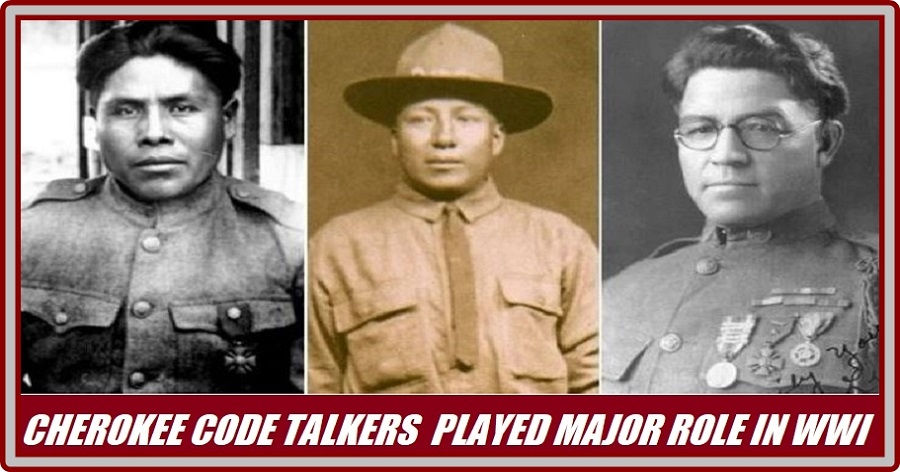

Choctaw code talkers served major communications function in World War I

- Dennis McCaslin

- Apr 27, 2019

- 7 min read

By Dennis McCaslin

In October 1918 the Americans were losing World War I, the Great War, when 19 men from Oklahoma’s Choctaw Nation set foot in southern France to fight for a country that did not even recognize them as citizens.

They hailed from places like Wright City, Oak Hill, Lester and Hochatown in southeast Oklahoma, and many came from the Armstrong Academy near Durant where they were told not to speak their native Choctaw language and were sometimes beaten for it.

The Choctaws arrived in southern France on Oct. 3, and although they were to have two more weeks of training, they found themselves on the front lines just three days later.

The war wasn’t going well. The Germans were able to tap into the American Army’s phone lines and learn the locations of the Allied forces. Codes were easily broken and Germany was poised to claim victory.

While the nineteen members of the Choctaw Nation played a significant role in the waning months of World World War I, their accomplishments have been overshadowed due in part to an intense focus on their counterparts from the Navajo tribe. Countless articles, books, documentaries and even movies have celebrated the “code talkers” who helped baffle the enemy by relaying messages in their native tongues have been produced about the Navajos while the Choctaw code talkers were never given their due until 2008.

The Navajo, with their history of opposing the United States in war, have proven in almost all aspects to be a more popular subject than the quiet, orderly, agrarian Choctaw Indians, who, in the early 19th century, adopted an American-style constitution and government, complete with elections and separation of powers. The Navajos also benefited in the history books because they served during the more “glamorous” second World War.

The Choctaw version of code talkers were a group of Choctaw Indians strictly from Oklahoma who pioneered the use of Native American languages as military code. Their exploits took place during the final months of World War I. The government of the Choctaw Nation maintains that the men were the first American native code talkers ever to serve in the US military.

Code talking, the practice of using complex Native American languages for use as military code by American armed forces, got its start during World War I. The German forces proved not only to speak excellent English but also to have intercepted and broken American military codes.

An American officer, Colonel A. W. Bloor, noticed a number of American Indians serving with him in the 142nd Infantry in France. Overhearing two Choctaw Indians speaking with each another around a campfire, he realized he could not understand them.

He also realized that if he could not understand them, the same would be true for Germans, no matter how good their English skills. Besides, many Native American languages have never been written down. With the active cooperation of his Choctaw soldiers, he tested and deployed a code, using the Choctaw language in place of regular military code.

The first combat test took place on October 26, 1918, when Colonel Bloor ordered a “delicate” withdrawal of two companies of the 2nd Battalion, from Chufilly to Chardeny. The movement was successful: “The enemy’s complete surprise is evidence that he could not decipher the messages”, Bloor observed.

Native Americans were already serving as messengers and runners between units. By placing Choctaws in each company, messages could be transmitted regardless if the radio was overheard or the telephone lines tapped.

In a postwar memo, Bloor expressed his pleasure and satisfaction. “We were confident the possibilities of the telephone had been obtained without its hazards.” He noted, however, that the Choctaw tongue, by itself, was unable to fully express the military terminology then in use

No Choctaw word or phrase existed to describe a “machine gun”, for example. So the Choctaws improvised, using their words for “big gun” to describe “artillery” and “little gun shoot fast” for “machine gun.”

“The results were very gratifying,” Bloor concluded.

Within 24 hours after the Code Talkers created the code, the tides of the battle had turned, and in less than 72 hours, the Germans retreated. The achievements were sufficient to encourage a training program for future Code Talkers, but the war was over in a few months.

When German officers were captured, they all asked what language the Allies were using. The only answer they received was “American.”

Little was said or written of the code talkers after World War I.

The earliest known mention in the media appears to have been 1928 when an Oklahoma City newspaper described their unusual activities.

The Choctaw themselves appear not to have referred to themselves as ‘code talkers’.

The phrase was not coined until during or after World War II. In describing their wartime activities to family members, at least one member of the group, Tobias W. Frazier, always used the phrase, “talking on the radio” by which he meant field telephone.

The Choctaw government awarded the code talkers posthumous Choctaw Medals of Valor at a special ceremony in 1986. France followed suit in 1989, awarding them the Fifth Republic’s Chevalier de l’Ordre National du Merite (Knight of the National Order of Merit).

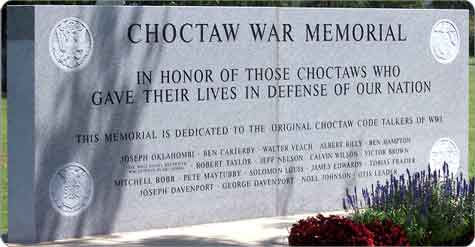

In 1995, the Choctaw War Memorial was erected at the Choctaw Capitol Building in Tuskahoma, Oklahoma. It includes a huge section of granite dedicated to the Choctaw Code Talkers.

On November 15, 2008, The Code Talkers Recognition Act of 2008 (Public Law 110-420), was signed into law by President George W. Bush, which recognizes every Native American code talker who served in the United States military during World War I or World War II, with the exception of the already-awarded Navajo, with a Congressional Gold Medal for his tribe, to be retained by the Smithsonian Institution, and a silver medal duplicate to each code talker.

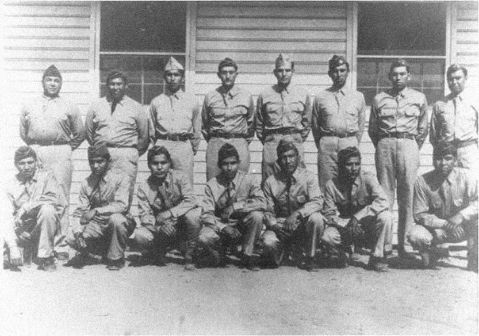

The men who made up the United States’ first code talkers were either full-blood or mixed-blood Choctaw Indians. All were born in the Choctaw Nation of the Indian Territory, in what is now southeastern Oklahoma, when their nation was a self-governed republic. Later, other tribes would use their languages for the military in various units, most notably the Navajo in World War II.

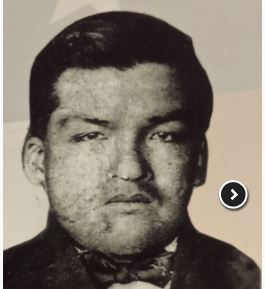

The 19 known Choctaw code talkers are as follows:

Albert Billy (1885–1958). Billy, a full blood Choctaw, was born at Howe, San Bois County, Choctaw Nation, in the Indian Territory. He was a member of the 36th Division, Company E.

Mitchell Bobb (January 7, 1895). Bobb’s place of birth was Rufe, Indian Territory Rufe, Oklahoma in the Choctaw Nation, his date of death is unknown. He was a member of the 142nd Infantry, Company E.

Victor Brown (1896–1966). Brown was born at Goodwater, Kiamitia County, Choctaw Nation.

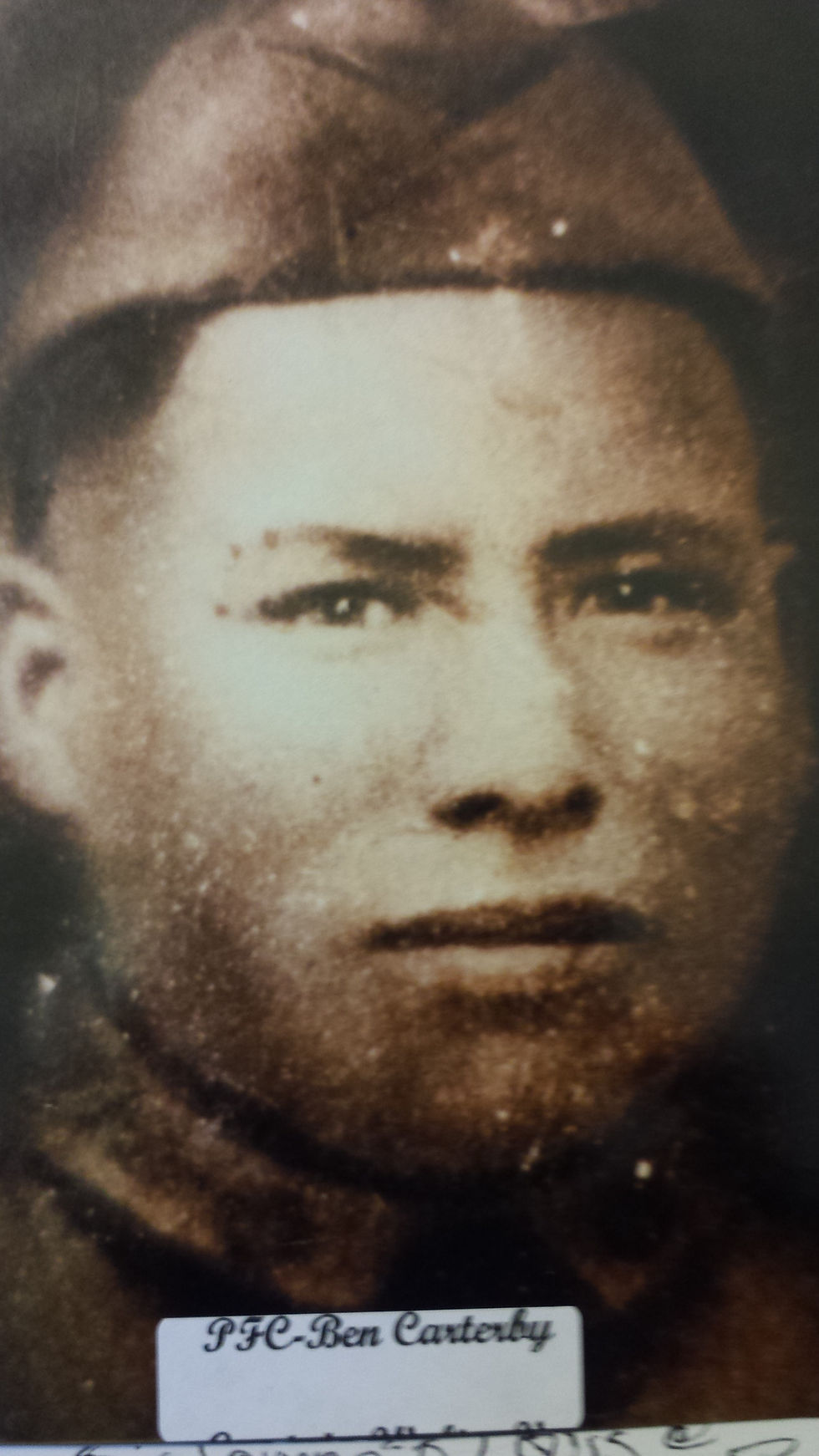

Ben Carterby (December 11, 1891 – February 6, 1953). Carterby was a full blood Choctaw roll number 2045 born in Ida, Choctaw County, Oklahoma.

Benjamin Franklin Colbert Born September 15, 1900 at Durant Indian Territory, died January 1964. He was the youngest Code Talker. His Father, Benjamin Colbert Sr, was a Rough Rider during the Spanish – American War.

George Edwin Davenport was born in Finley, Oklahoma, April 28, 1887. He enlisted in the armed services in his hometown. George may also have been called James. George was the half-brother to Joseph Davenport. Died April 17, 1950.

Joseph Harvey Davenport was from Finley, Oklahoma, Feb 22, 1892. Died April 23, 1923 and is buried at the Davenport Family Cemetery on the Tucker Ranch.

James (Jimpson) Morrison Edwards (October 6, 1898 – October 13, 1962). Edwards was born at Golden, Nashoba County, Choctaw Nation in the Indian Territory. He was a member of the 142nd Infantry, Company E.

Tobias William Frazier (August 7, 1892– November 22, 1975). (A full blood Choctaw roll number 1823) Frazier was born in Cedar County, Choctaw Nation. He was a member of the 142nd Infantry, Company E.

Benjamin Wilburn Hampton (a full blood Choctaw roll number 10617) born May 31,1892 in Bennington, Blue County, Choctaw Nation, Indian Territory, now Bryan County, Oklahoma. He was a member of the 142nd Infantry, Company E.

Noel Johnson - Code Talker Noel Johnson, 142nd Infantry, Born August 25, 1894 at Smithville Indian Territory. He attended Dwight Indian Training School. His World War I draft registration stated he had weak eyes. Great Niece Christine Ludlow said he was killed in France and his body was not returned to the US.

Otis Wilson Leader (a Choctaw by blood roll number 13606) was born March 6, 1882 in what is today Atoka County, Oklahoma. He died March 26, 1961 and is buried in the Coalgate Cemetery.

Solomon Bond Louis (April 22, 1898 – February 15, 1972). Louis, a full blood Choctaw, was born at Hochatown, Eagle County, Choctaw Nation, in the Indian Territory. He was a member of the 142nd Infantry, Company E. He died in Bennington, Bryan County, Oklahoma in 1972.

Pete Maytubby was born Peter P. Maytubby (a full blood Chickasaw roll number 4685) on September 26, 1892 in Reagan, Indian Territory now located in Johnston County, Oklahoma. Pete was a member of the 142nd Infantry, Company E. He died in 1964 and is buried at the Tishomingo City Cemetery in Tishomingo, Oklahoma.

Jeff Nelson (unknown). He was a member of the 142nd Infantry, Company E.

Joseph Oklahombi (May 1, 1895 – April 13, 1960). Oklahombi – whose surname in the Choctaw language means man- killer – was born at Bokchito, Nashoba County, Choctaw Nation in the Indian Territory. He was a member of the 143rd Infantry, Headquarters Company. Oklahombi is Oklahoma’s most decorated war hero, and his medals are on display in the Oklahoma Historical Society in Oklahoma City.

Robert Taylor (a full blood Choctaw roll number 916) was born January 13, 1894 in Idabel, McCurtain County, Oklahoma (based on his registration for the military in 1917). He was a member of the 142nd Infantry, Company E.

Charles Walter Veach (May 18, 1884 – October 13, 1966). (Choctaw by Blood roll #10021) Veach was from Durant, OK (Blue County I.T.)he served in the last Choctaw legislature and as Captain of the Oklahoma National Guard, 1st Oklahoma, Company H which served on the TX border against Pancho Villa and put down the Crazy Snake Rebellion.

He remained Captain when Company H. 1st Oklahoma, was mustered into Company E. 142nd Infantry, 36th Division, U. S. Army at Ft. Bowie, TX in October 1917. After World War II he represented the Choctaw Nation on the Inter-tribal Council of the 5 Civilized Tribes. He is buried in Highland Cemetery, Durant, Oklahoma.

Calvin Wilson Calvin was born June 25, 1894 at Eagletown, Eagle County, Choctaw Nation, Indian Territory. He was a member of the 142nd Infantry, Company E. His date of death is unknown. Wilson’s name is misspelled in military records as “Cabin.”

Comments